I Watched Him Overdose

What it felt like, as a teenager, watching drugs ravage my home and lead to an overdose.

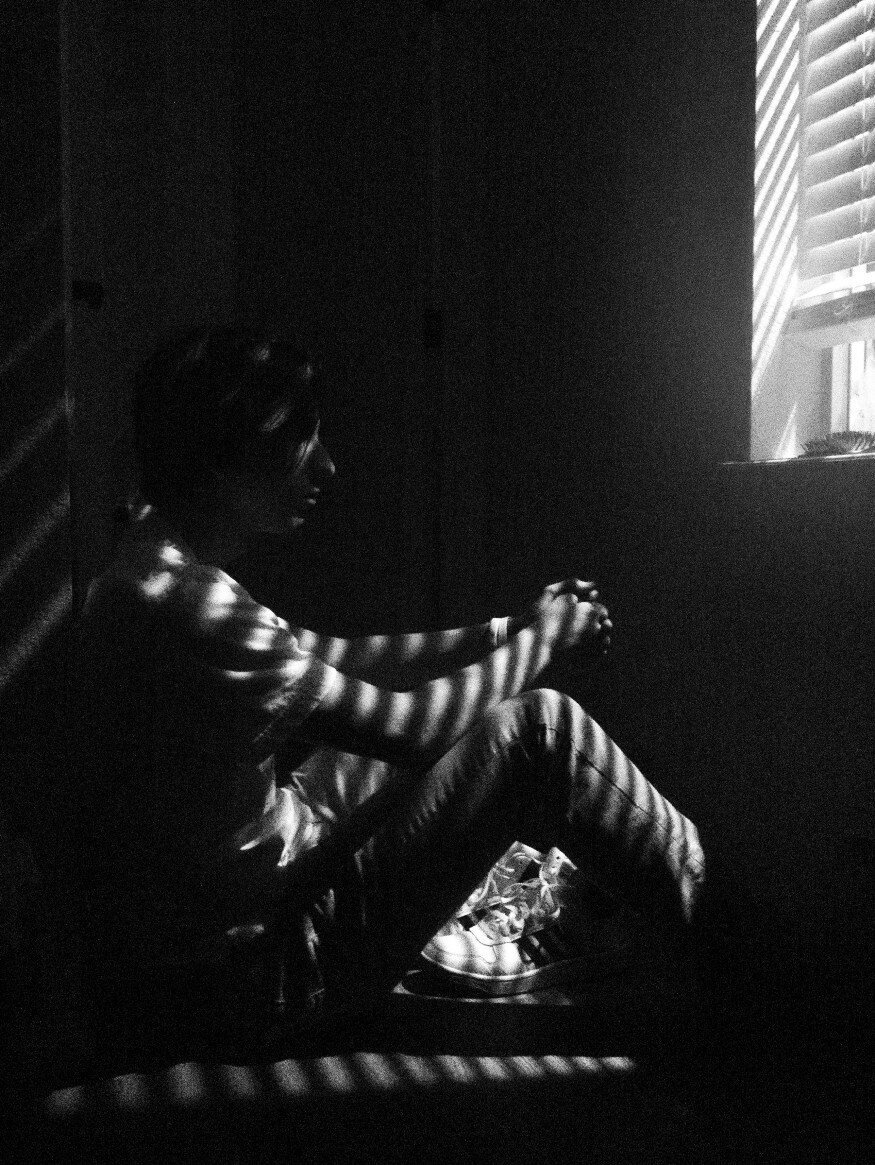

Photo by Aidan Roof on Pexels

When I was 16, my mom told me she had starting dating someone new. I hadn’t heard anything about him prior to this. She said he was a good deal younger than her and had been working as a waiter, but having lost his job, he’d be coming to stay with us for a while. She also said he had had problems with drug addiction but was now clean. His youth, unemployment, and difficulties with addiction all made me wary, but I was going through a philosophical awakening at the time — having just recently discovered the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche, which I interpreted as a call to freedom from established values and an end to all judgment. I purposefully sought to look past what others might be critical about. Moreover, as to his drug use, I myself had come as of late to recognize the pleasures of smoking marijuana. I welcomed him with an open mind.

When I first met Phil, I was surprised by how young he looked. He was not only younger than my mother, but he also looked considerably younger than his age. He occupied, for me, that strange inter-generational space where I was unsure whether to interact with him as I would an established adult or one of my peers. Still, in reality, he was well into his 30s, and I was not yet an adult. He brought with him some gifts: books on philosophy and psychology and writing. It was from him that I received my first copy of Strunk’s The Elements of Style (an essential book for any writer). Another among them was Freud’s Dora, a case study of Freud’s work with a woman with hysteria. Others that he brought I had already, such as Carl Jung’s Synchronicity. These books, playing on my interests and sentimentality, confirmed to me how right I had been not to stereotype him. He was a tortured soul, but a thinking, feeling mind nonetheless.

As time progressed, things were nice, though they had an eerie feeling of simulation, as if things were not what they seemed. It is a feeling that builds in the gut when you notice signs that things are not altogether normal, but have yet to recognize the hidden implications and sequelae of those subtle incongruities. For example, Phil would cook and clean — he was, in fact, quite good at cooking, having worked as a chef for sometime — and he was polite and patient, and my mother was happy. However, Phil would drink habitually; he’d have six beers every night. He’d sit down to the table with three and get another three after dinner. He wouldn’t act particularly drunk or anything. It wasn’t necessarily a bad thing; it was just the drinking of six beers. It is things like this that struck me as vague auguries at the time. I couldn’t point to what was wrong with that, but something didn’t feel right. After I had read a couple of the books he brought, and tried to strike up conversation with him about them, he told me that he hadn’t actually read any of them himself, which I found odd as they were all worn and stained by time.

Time went on and Phil’s cooking became less frequent, his cleaning stopped altogether, and his beers ramped up to 12 a night. He had arrived a muscular, youthful-looking man, but as the weeks went by his belly began to grow and flab accumulated on his face and arms. He began to physically and behaviorally morph into someone other than the person who had been originally presented when they entered our home. I remember my first time riding in the car with my mom and Phil, with him driving. He drove as if we were being chased by the Devil. He drove with a near-suicidal disregard. He drove like someone hungry to consume the space between them and anything in front of them, so he would accelerate to the car’s limit and weave in and out of traffic. And as I would talk to him, in our occasional and short interactions around the house, I would notice that he was missing from himself. With bloodshot, empty eyes, he would say things that, if not completely nonsensical, would approach it. Often he would just grunt or wave his hand to communicate.

My mother had always been somewhat of a high-functioning addict herself. I would be frustrated as a child when she would always refuse to drive me anywhere at night, due to her having taken “something for a headache.” Her nightstand was home to bottles of Vicodin so large you’d think they were prescribed to last a lifetime, yet they would be replaced with relative frequency. But she’d take these pills at the end of each day, laying on the couch and slipping into a benumbing high. It didn’t have much effect on her life, and she was an employed, functioning individual. However, I suppose this made her all the more susceptible to Phil’s influence. Soon, she too started to be a shadow of herself. She seemed perpetually confused and lost in a dream-like haze. I would talk to her, and it was as if her eyes couldn’t really focus on anything; it was as if she was looking through me. She could hardly remember anything that was said or done. She began to dress differently, act differently, and listen to different music. From a confluence of youthful naïveté, filial pedestaling, and interest in psychiatry, I wondered if she had early-onset Parkinson’s. She did not.

Our once clean home degraded into complete filth. With remarkable rapidity, the white walls were blackened by stains and scuffs. There was a growth of black mold behind the couch. Our two unwashed dogs would scratch at themselves incessantly as fleas and ticks infested their matted hair. The tile floor became coated in a sticky layer of dried urine from the two dogs; I remember as I’d occasionally try to clean it how it would turn the water from the mop into a sort of slush. You couldn’t really lift it up from the floor; you could only move it around. Ticks were everywhere: in my room, on my bed, and on my body. As I walked around the house, I’d often feel something like a grape popping under the sole of my shoe. It was invariably a tick the size (and general appearance) of a raisin.

There is something indescribable that happens to you in conditions such as these. Our souls were all dragged down as if they were stuck in some moral quicksand. I tried to resist it. I would grab my mother by the shoulders and look in her eyes and tell her how insane this all was. I’d fight with Phil for being a bane that had brought us so low. But, at the end of the day, I would just retreat and resign. What was the point of trying to clean what would never really be clean again? What was the point of trying to argue with those deaf ears and lifeless eyes? What was the point of anything? It became too much to look at directly.

I’m still filled with painful regret and shame as I picture Stitch, our tiny, orange-brown Pomeranian, scratching without end at his patchy fur. I’d give him and our German Shepherd Rottweiler mix, Kujo, a bath occasionally. I remember Stitch’s fragile body in my hands and how he’d growl and snap at me. His mind was as irritated and raw as his skin was. He was no longer the same animal; he had become frantic and aggressive. I remember walking past him up the stairs, thinking to myself I wish I could help you, but I can’t even help myself. My room came to match the rest of the house: Trash covered the floor, and grime was caked on the walls. My carpet was once a light tan color, but it grew increasingly filthy, and everyone’s refusal to step on it without shoes, including myself, quickly expedited its discoloration, and soon it was nearly completely black. I’d steal my mom’s Vicodin and take them when I was at school, though I soon dropped out. At home, I’d smoke from morning till night.

I confined myself to my room, became reliant on myself, and explored my mind. I started selling weed, mostly so that I’d have weed to smoke myself. I’d eat four hot pockets a day, two at 10 A.M. and the other two at 2 P.M., and sometimes a family-size bag of Doritos. I quickly shed pounds from my body. I remember a young man from my neighborhood, Erick, mocking me and saying, “You used to be the fat kid and so now you want to be the skinniest one!”

I still had bunk beds that I had gotten when I was a small child. I had desperately wanted them, even though I was an only child, but as my body outgrew the length of that twin-size mattress, it became a sort of mocking reminder of the stagnation and decay all around me. I took apart the large frame, complete with a built-in desk and drawers, and I dragged them all to the street in front of the house. When I was done, nothing but two twin-size mattresses and a TV stand remained. I put the mattresses side by side and threw a king-size sheet over them. I saved up money and bought several cans of paint: a couple light blue, one white, one gray, and one yellow. I also bought glow-in-the-dark paint and stars. I painted every inch of the walls and ceiling with the light blue. Then, I painted clouds with swirls of white and gray, and, finally, I put a yellow dot on the ceiling. Then, I circled the dot with yellow paint, and circled that circle, until I had a veritable sun on my ceiling. I painted over the sun with the glow-in-the-dark paint and covered the room with the glow-in-the-dark star stickers. With a flip of the switch, it would transform day into night, sun into moon, and vice-versa. As it had felt in my mind, I now had my own little world in that room. I’d smoke and lay on my back, look up at the sky, and think. And I’d write down what I thought, hoping to one day be a famous philosopher like Nietzsche.

Phil was constantly getting sick and infected. He would get grotesque boils the size of golf balls, and his arm would swell with pus — perhaps because of the needles, the hampered immune system, or both — and he’d go and get it drained, returning with Frankenstein-esque stitches, only to do it all over again. I learned at some point from Phil that he had overdosed six times previously. I have no desire to group marijuana in with the drugs Phil used, which were, frankly, all of them. He would use heroin, cocaine, crack, LSD, methamphetamine, pot, pills — anything he could find. I once saw him on the front porch inhaling tiny canisters of nitrous oxide (aka laughing gas); I even tried one myself. However, intemperance is intemperance, and he, who had abused his whole body, and I, who had abused my lungs, both came down with a bad bout of bronchitis. Neither one of us ceased our recreational activities on account of our strained breaths. One of the mornings, in the midst of our shared bronchitis spell, my mother told me Phil had stopped breathing in the middle of the night, and the ambulance had come to resuscitate him. Apparently, I had slept through the whole affair. Later that day, they left out of town overnight; I forget for what reason. I lied there that night horrified as I coughed and drew painful breaths; I thought that, as I lied alone in that house, I too would stop breathing, and there’d be no one to call an ambulance for me. I fell asleep with 911 typed into the dial pad on my phone. I didn’t stop breathing, and they returned the next day.

The day after they returned, I was sitting in my room reading and feeling much better. I heard my mom scream, “Help! Help!” I rushed from the room into the hallway. Convulsing with panic, she forced out the words: “Phil’s not breathing.” I promised in the subtitle to tell you how it felt to see someone overdose at 17 years old. If I’m to be completely honest, a rare calm and clarity of mind came over me. I said, “You need to call 911 and tell them the address and that he’s not breathing. Then, I need you to go to my room, get all the bags of weed, and put it in the backyard by the fence. Where is he?” She pointed me to her bedroom.

As I entered, I saw through the bedroom to the bathroom, where he was lying on his back on the floor. As I approached him, I was astonished by his appearance. His skin was blue with purple veins showing all over. His body looked twice its normal size, with every part of him swollen. His face had an unconscious and lifeless lack of expression, but he was doing something that seemed like a sort of inhuman snoring. A loud, clicking sound would emanate from his throat, and his head would move back as it happened. A series of 3 or 4 clicks would rattle off, with each his head would jerk back some, and then they’d stop for a moment, and another series of clicks would start. His distorted and struggling body seemed out of keeping with the peaceful look of death on his face. I had failed the CPR class I took at school, but I still remembered some of what I had learned, like where to place one’s hands for chest compressions and to do it to the beat of “Stayin’ Alive” by The Bee Gees. His body was cold, moist, and spongy. I performed chest compressions on him until I heard the ambulance pull up out front. I walked over to my room and waited until the EMTs all ran over to him. I then walked out and down the stairs. As I walked down the steps, I heard them say that it was the same guy from the other night, an OxyContin overdose, and that they were going to intubate him. I heard Phil cough and choke, and then immediately come back to life. I walked out the back door and over to the fence, grabbed my bags of weed, jumped over the fence, and went to a friend’s house. (I had sought to get my stash out of the house, in case the police came.)

So what did it feel like to watch someone overdose? At the time, I felt nothing but calm and control. Later that night, frustration at the whole situation washed over me, including my fear of dying two nights earlier — when Phil had actually overdosed then too, and so there had been no danger of my ceasing to breathe from bronchitis as I thought he did — and I sobbed with abandon. I cried without control. I suppose that’s how it felt to watch someone overdose, once the anesthetic adrenaline of the moment had worn off.